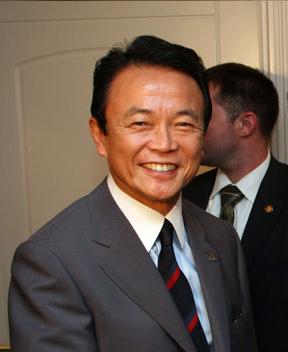

Prime Minister Aso Taro officially opened the extraordinary session of the Diet with his first policy address.

Press coverage of the speech has uniformly characterized it as taking to the offensive to the DPJ.

In the first portion of the speech, Mr. Aso suggested that in its opposition to government plans, the DPJ has put the people's livelihoods second or third, not first as its slogan proclaims. He declared that he would attack the DPJ on its own terms, challenging the DPJ's claim to speak for the people against the LDP-Komeito coalition.

To do so, he offered his three-pronged economic plan focused on (1) fighting the recession, (2) medium-term fiscal reconstruction, and (3) long-term structural reform in the interest of economic growth. Under the first scheme, he pledged tax cuts designed to provide immediate relief for Japanese citizens, although Mr. Aso called particular attention to farmers, fishermen, and small- and medium-sized businessmen. He appealed to the DPJ to support the supplementary budget that includes the tax cut, or at least engage in a debate and offer a bill of its own. Meanwhile he mentioned fiscal reconstruction only to state that it is off the table for the foreseeable future. Fiscal reconstruction, Mr. Aso said, is a means to an end, namely Japanese prosperity. Unless Japan's economy is growing it is misguided to talk of fiscal rectitude. (It would be nice, however, if Mr. Aso weren't so cavalier about the idea that if Japan doesn't find a way to both stimulate its economy and fix its budget situation, the medium- to long-term prognosis for the Japanese economy is dismal. Given how little space Mr. Aso devotes to this second point, it appears that it was included because it had to be included, but that Mr. Aso's government will particularly concerned with the budget. The public, after all, isn't exactly clamoring for a balanced budget.)

Finally he turned to his version of structural reform, although he did not use the now-tainted term. Clearly drawing on the ideas experienced in his March Chuo Koron article, he called for restoring confidence in the pensions and health care systems. On health care, he rejected a wholesale revision of the April eldercare system, suggesting that the problem was that it was "poorly explained" by the government and asking for patience. Turning to the "youth" problem, he called for a minimum wage increase and reviewing the labor dispatch problem. He included two leftovers from the Fukuda government, the pursuit of a consumer affairs agency and the need to cut government waste. On the latter, however, he fudged by declaring that the task is making government more efficient and more responsive to the public, but not necessarily a less expensive government. He called for greater regional decentralization — as he has articulated before — and said that he's aiming for fifty percent agricultural self-sufficiency. And he concluded with a long explanation of his government's foreign policy goals, starting with "stable and prosperous" relations with Japan's neighbors, moving on to greater involvement in solving global problems, supporting young democracies in the region, and reaffirmed the centrality of the resolution of the abductions issue for Japan-North Korea normalization to proceed. He then, in a move that undoubtedly pleased Washington, appealed to the DPJ to recognize the importance of the US-Japan alliance and reiterated the importance of the MSDF's refueling mission in the Indian Ocean.

This was a campaign speech masquerading as a policy address.

It's not just a matter of his redirecting questions back at the DPJ; it's that he doesn't really seem that interested in articulating policy except in exceedingly broad strokes. To call it a laundry list would be insulting to laundry lists. Consider the two policy addresses Fukuda Yasuo gave to open last year's extraordinary session and this year's ordinary session. The conditions facing Mr. Fukuda in both instances were little different than those facing Mr. Aso. But Mr. Fukuda in both instances worked to call attention to the gravity of the problems facing Japan and tried to articulate a way out. His speech this time last year was less detailed, but he laid out his priorities and signaled that he would govern differently. His January address, however, was full of specific policies to address a range of problems. And he did not shrink from stating just how serious Japan's current predicament is.

With his optimism, Mr. Aso breezed over the latter — his belief in Japan's latent power seems to have him convinced that Japan can weather anything. His optimism is undoubtedly an asset. The public will likely be pleased to hear a prime minister who believes that things will get better and that there will be an end to their insecurities. In this, Mr. Aso addressed one of the major complaints about Koizumi Junichiro, namely that he put destruction before construction.

But I don't think his strategy of reclaiming the momentum by calling out the DPJ will work. I see the political logic: Mr. Aso needs the public to forget that the LDP is responsible for having brought Japan to where it is today and to see the DPJ as responsible for having created gridlock for putting party before country. (Of course, this is exactly what Mr. Aso is doing too.) But will the public buy it? The public seems to be more interested in things getting done than in this kind of political gamesmanship. And I doubt that a single speech will make voters forget years of LDP maladministration.

Morever, at MTC argues, I don't think the DPJ will be cowed by Mr. Aso's exhortation to put country first. (The McCain-Aso comparisons continue to mount...)

The DPJ shouldn't shy away from a policy debate. Indeed, they should relish the opportunity to ask Mr. Aso for details about what exactly he plans to do. The DPJ should be insistent on discussing whether the stimulus package pushed for by the government will actually address the public's concerns, whether he thinks the current eldercare system is really working for Japan's citizens, whether the prime minister should be so concerned about foreign policy at a time like this. There's the assumption in this speech that there's one best way to solve Japan's problems. There's not. And with the DPJ in control of the upper house, any solution must be an LDP-DPJ solution. Under Mr. Fukuda the LDP appeared to think that cooperation in the divided Diet means dictating terms to the DPJ. Under Mr. Aso it appears that things will be little different.

Mr. Aso is vulnerable. He can parry and thrust on these policy questions, but in being drawn into a protracted policy debate with the DPJ, he will look less like the newly ordained leader of the nation and more like the leader of the decrepit, old LDP with its anti-Midas touch. The DPJ must not allow Mr. Aso to portray himself as transcending politics and parties, as acting only with the country's interests at heart. Mr. Aso's genuine love for Japan may make this hard — it's a pretty convincing act — but if the DPJ stands fast on policy questions and allows the Aso cabinet to self-destruct, it will be able to halt the Aso offensive.

Press coverage of the speech has uniformly characterized it as taking to the offensive to the DPJ.

In the first portion of the speech, Mr. Aso suggested that in its opposition to government plans, the DPJ has put the people's livelihoods second or third, not first as its slogan proclaims. He declared that he would attack the DPJ on its own terms, challenging the DPJ's claim to speak for the people against the LDP-Komeito coalition.

To do so, he offered his three-pronged economic plan focused on (1) fighting the recession, (2) medium-term fiscal reconstruction, and (3) long-term structural reform in the interest of economic growth. Under the first scheme, he pledged tax cuts designed to provide immediate relief for Japanese citizens, although Mr. Aso called particular attention to farmers, fishermen, and small- and medium-sized businessmen. He appealed to the DPJ to support the supplementary budget that includes the tax cut, or at least engage in a debate and offer a bill of its own. Meanwhile he mentioned fiscal reconstruction only to state that it is off the table for the foreseeable future. Fiscal reconstruction, Mr. Aso said, is a means to an end, namely Japanese prosperity. Unless Japan's economy is growing it is misguided to talk of fiscal rectitude. (It would be nice, however, if Mr. Aso weren't so cavalier about the idea that if Japan doesn't find a way to both stimulate its economy and fix its budget situation, the medium- to long-term prognosis for the Japanese economy is dismal. Given how little space Mr. Aso devotes to this second point, it appears that it was included because it had to be included, but that Mr. Aso's government will particularly concerned with the budget. The public, after all, isn't exactly clamoring for a balanced budget.)

Finally he turned to his version of structural reform, although he did not use the now-tainted term. Clearly drawing on the ideas experienced in his March Chuo Koron article, he called for restoring confidence in the pensions and health care systems. On health care, he rejected a wholesale revision of the April eldercare system, suggesting that the problem was that it was "poorly explained" by the government and asking for patience. Turning to the "youth" problem, he called for a minimum wage increase and reviewing the labor dispatch problem. He included two leftovers from the Fukuda government, the pursuit of a consumer affairs agency and the need to cut government waste. On the latter, however, he fudged by declaring that the task is making government more efficient and more responsive to the public, but not necessarily a less expensive government. He called for greater regional decentralization — as he has articulated before — and said that he's aiming for fifty percent agricultural self-sufficiency. And he concluded with a long explanation of his government's foreign policy goals, starting with "stable and prosperous" relations with Japan's neighbors, moving on to greater involvement in solving global problems, supporting young democracies in the region, and reaffirmed the centrality of the resolution of the abductions issue for Japan-North Korea normalization to proceed. He then, in a move that undoubtedly pleased Washington, appealed to the DPJ to recognize the importance of the US-Japan alliance and reiterated the importance of the MSDF's refueling mission in the Indian Ocean.

This was a campaign speech masquerading as a policy address.

It's not just a matter of his redirecting questions back at the DPJ; it's that he doesn't really seem that interested in articulating policy except in exceedingly broad strokes. To call it a laundry list would be insulting to laundry lists. Consider the two policy addresses Fukuda Yasuo gave to open last year's extraordinary session and this year's ordinary session. The conditions facing Mr. Fukuda in both instances were little different than those facing Mr. Aso. But Mr. Fukuda in both instances worked to call attention to the gravity of the problems facing Japan and tried to articulate a way out. His speech this time last year was less detailed, but he laid out his priorities and signaled that he would govern differently. His January address, however, was full of specific policies to address a range of problems. And he did not shrink from stating just how serious Japan's current predicament is.

With his optimism, Mr. Aso breezed over the latter — his belief in Japan's latent power seems to have him convinced that Japan can weather anything. His optimism is undoubtedly an asset. The public will likely be pleased to hear a prime minister who believes that things will get better and that there will be an end to their insecurities. In this, Mr. Aso addressed one of the major complaints about Koizumi Junichiro, namely that he put destruction before construction.

But I don't think his strategy of reclaiming the momentum by calling out the DPJ will work. I see the political logic: Mr. Aso needs the public to forget that the LDP is responsible for having brought Japan to where it is today and to see the DPJ as responsible for having created gridlock for putting party before country. (Of course, this is exactly what Mr. Aso is doing too.) But will the public buy it? The public seems to be more interested in things getting done than in this kind of political gamesmanship. And I doubt that a single speech will make voters forget years of LDP maladministration.

Morever, at MTC argues, I don't think the DPJ will be cowed by Mr. Aso's exhortation to put country first. (The McCain-Aso comparisons continue to mount...)

The DPJ shouldn't shy away from a policy debate. Indeed, they should relish the opportunity to ask Mr. Aso for details about what exactly he plans to do. The DPJ should be insistent on discussing whether the stimulus package pushed for by the government will actually address the public's concerns, whether he thinks the current eldercare system is really working for Japan's citizens, whether the prime minister should be so concerned about foreign policy at a time like this. There's the assumption in this speech that there's one best way to solve Japan's problems. There's not. And with the DPJ in control of the upper house, any solution must be an LDP-DPJ solution. Under Mr. Fukuda the LDP appeared to think that cooperation in the divided Diet means dictating terms to the DPJ. Under Mr. Aso it appears that things will be little different.

Mr. Aso is vulnerable. He can parry and thrust on these policy questions, but in being drawn into a protracted policy debate with the DPJ, he will look less like the newly ordained leader of the nation and more like the leader of the decrepit, old LDP with its anti-Midas touch. The DPJ must not allow Mr. Aso to portray himself as transcending politics and parties, as acting only with the country's interests at heart. Mr. Aso's genuine love for Japan may make this hard — it's a pretty convincing act — but if the DPJ stands fast on policy questions and allows the Aso cabinet to self-destruct, it will be able to halt the Aso offensive.